|

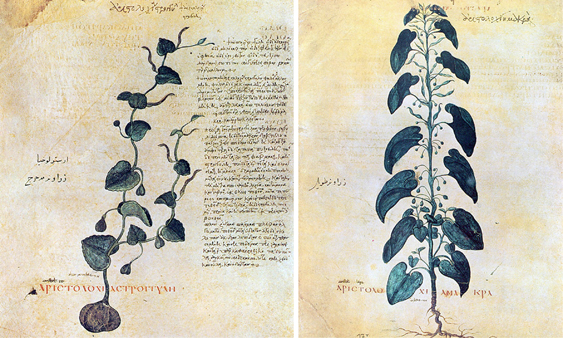

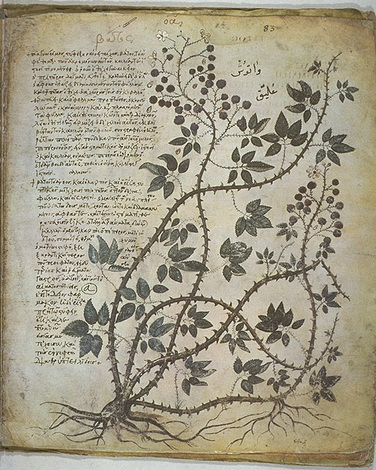

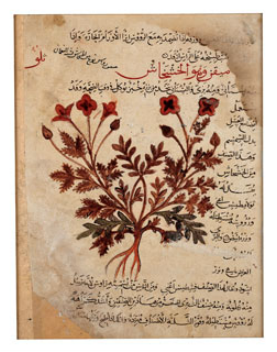

Post originally made on March 17, 2015 on the EcoEvoLab Blog (ecoevolab.com) This post was inspired by recent conversations in our department regarding the contemporary place of natural history in science (e.g. Are students disregarding natural history for the sake of their scientific questions? Does natural history without a broader scientific question even have a place in science? Why the lack of respect for purely descriptive science?) While each of these questions could stand alone as posts, I am not going to address them, at least directly. Instead, the importance of natural history is one thing, I think, that no one denies. The first natural historians were artists, so through the next few of my posts I’m going to acknowledge some influential pieces of incredible art and natural history. The five volumes of De Materia Medica consist of over 600 plants, animals and minerals, as well as near 1000 medicinal cocktails. Each of the illustrated entries gives natural history details including recognition tips, pharmacological effects, and even cautionary notes. The Roman physician Dioscorides classified the various plants and substances into five volumes (e.g. volume 1 focuses on aromatics– oils and ointments, and the useful plants such as cinnamon, mastic or peach; volumes 3-4 focus on herbs, roots and seeds). According to science historians, De Materia Medica is one of the most enduring works of natural history in history, not replaced for about 1,500 years. It was one of the earliest scientific manuscripts translated from Greek into Arabic in the 9th century when it quickly became the basis of Islamic pharmacology. Hand-copied and illustrated manuscripts were distributed widely and never left circulation, unlike other classical documents. Eventually Dioscorides’ work was revised during the Renaissance. Interestingly, perhaps history is having the same conversation that we are: can natural history ever be purely descriptive? De Materia Medica was not a purely observational account of the wonders of the natural world. Though accurate in it’s observational drawings (though some copies include artistic tendencies towards symmetry and stylization), it had the purpose of understanding the natural world to answer scientific questions about medicine.

Thanks to Wikipedia and the Aga Khan Museum online gallery for information and images.

0 Comments

Post originally published on August 6, 2014 on the EcoEvoLab Blog (ecoevolab.com)

Remember that philosopher who proposed that everything was made of fire, air, earth and water? Besides his name, (his name is Empedocles) what most of us probably don’t know about this guy is that he predicted a sort of natural selection circa 600 BC. To understand how, first we must understand how he believed these four elements operated in the world. It was in a poem, On Nature, where Empedocles lays forth these four elements as the basic building blocks of all things. But these elements can neither be combined nor divided without the two opposing forces of love and strife. Love blends the elements while strife pulls them apart. Continual alternation between the forces creates cycles of formation and dissolution1. It is never the case that any of the elements appear or disappear—it is everything made from these elements that appear and disappear. As part of the cycling of love and strife, Empedocles describes the development of a cosmos and the development of animals. In writing about the development of animals, we see some of his insights into natural selection. He writes that there “sprang up many faces without necks, arms wandered without shoulders, unattached, and eyes strayed alone, in need of foreheads…”. These vagrant parts become assembled into viable creatures by the force of love (and somewhat randomly). Many of the creatures created by love soon disappear because the parts are not well suited for each other. It is strife that is responsible for condemning these creatures to disintegration if they are unable to survive. Sure, Empedocles didn’t mean to comment on evolution as we know it… but he did dream up a force that would allow complex creatures to survive if their parts were well suited in combination, and that worked against creatures with parts that were not. It is a rather elegant theory for the time. So now… remember that philosopher who (kind of) predicted natural selection and thought that everything was made of fire, air, earth and water? Thank you to the “timeline” in Essential Readings in Evolutionary Biology by Ayala and Avise for the idea, and the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy for more information! 1. ”cycles”: the extremes of the cycles and the number of cycles seem up for debate by interpreters of the texts, but read in greater detail at Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. The title of this blog, The Science Desk of Shannon LJ Bayliss, is not a promise to keep you up to date on breaking scientific news. No, it’s just about my life and science because I believe that everything in our lives can tell a scientific story.

Welcome. I hope you learn something sometimes. |

Let's see, shall we.CategoriesArchives

October 2020

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed