|

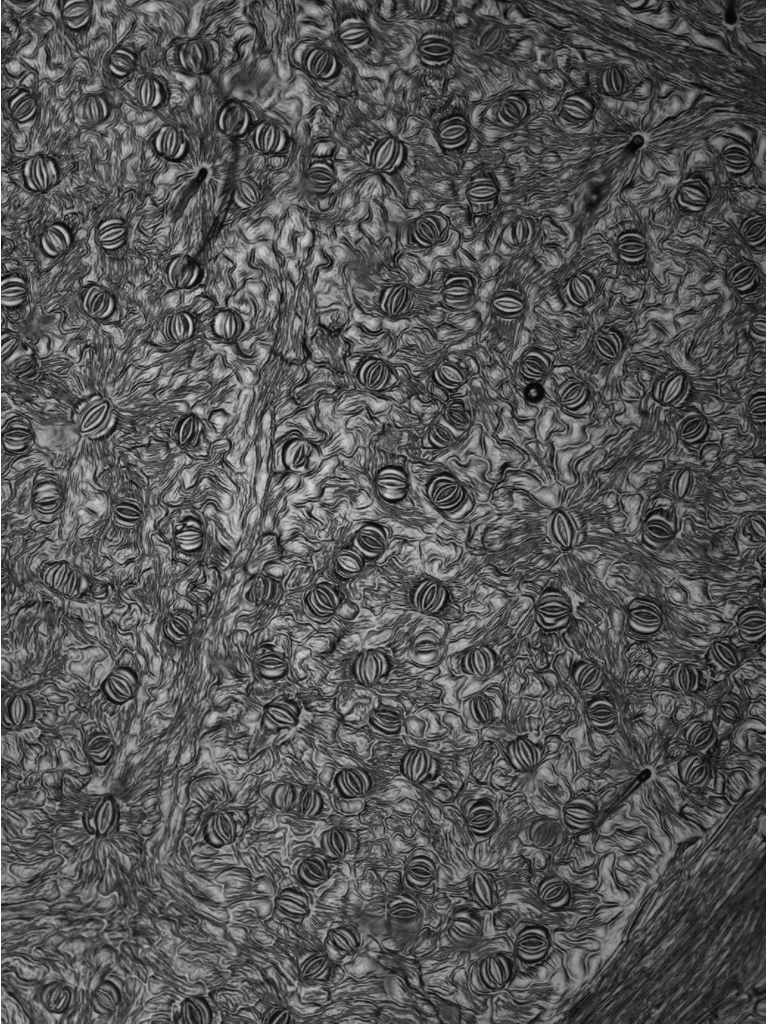

This is a photograph of a leaf surface of a narrowleaf cottonwood (Populus angustifolia) taken under a light microscope (at...checking lab notebook for level of magnification...). All you need to get imprints of leaf surfaces is glass microscope slides, transparent scotch tape, and clear nail polish. The prominent oval shapes in the photograph are stomata (singular: stoma). Stomata are pores that let stuff in and out of the leaf. In other words, they control the movement of gases in and out of the leaf (carbon dioxide used for photosynthesis and water out via transpiration). Variation in the size, the number, and the location (top or bottom of leaf) of stomata on leaf surfaces are a few ways that plants can control water loss, and thus are important to plant function.

Trivia: Do plants typically have a higher density of stoma on the top or the bottom surface of their leaves?

0 Comments

Many of the teas I drink provide an uplifting, generally encouraging message with each bag, similar to the inner foil of bite-sized Dove chocolates, like "love is infinite", "let your heart speak to others' hearts", or "teach your grandma to take a selfie". A few days ago, my heart, in anticipation of a tea message, was getting pumped up to start the day off right. But when I read my message, my happy heart thudded to the ground. The message read, “an attitude of gratitude brings opportunities”. Should I be grateful today so that doors open for me? Ahh ha! …I should be more grateful so that doors open for me. O.M.G., am I only grateful because doors open for me? It seemed that my tea bag went full-on biology on me: my usual good morning, yogi tea turned into good morning, Richard Dawkins; everything we do must have some sort of evolutionary selective basis, even the nice things—and my tea bag wanted me to remember that. Yes, I know what the yogi tea brand meant by that message, and no, I’m not cynical. I relish in a good inspirational quote from an anonymous source, my eyes get wet at the thought of anything grandiose or beyond our solar system, and, I’m definitely a sucker for the promises that many teas make (“detox, de-stress, comfort, rejuvenate, and soothe”, all in one?!). But, again, this morning I received the message “the only tool you need is kindness”, and I just can’t stop thinking about it.

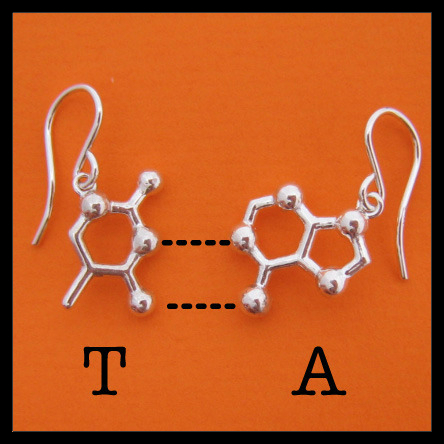

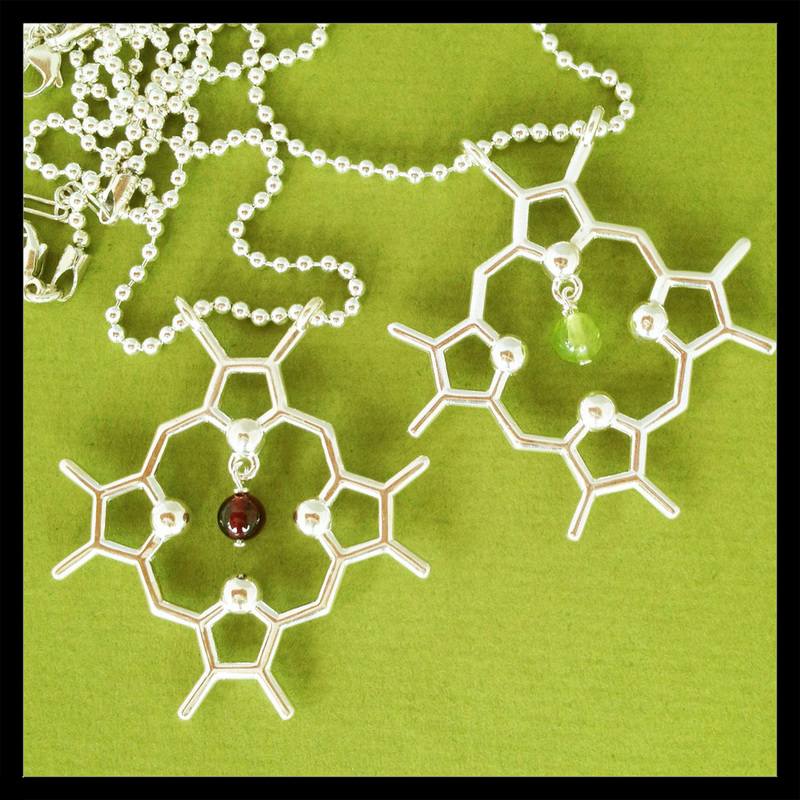

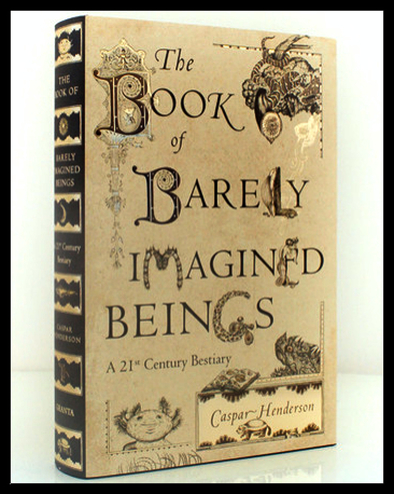

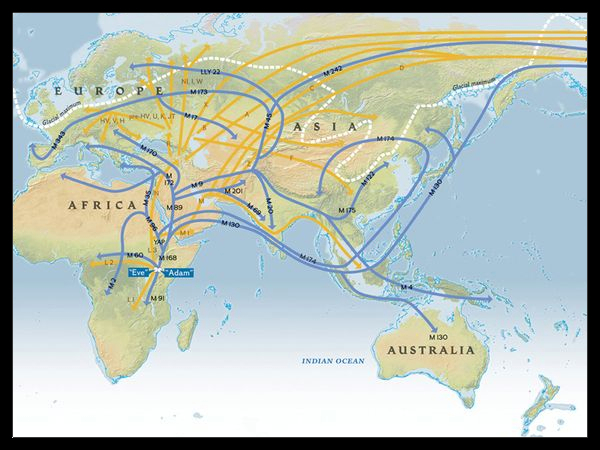

Being a biologist can be burdensome when you simply want to drink your tea. Last year I wrote "The first annual holiday gift-giving guide from Eco-Evo Lab". While I complete the assignment that I gave myself for this holiday season, I'll re-post last year's list. Buying gifts when you have to buy gifts is hard. For this holiday season, I’ve put together a list of ideas for your scientifically inclined loved ones (although many of these gifts would be great for anyone). The first five are personal favorites. Number 1 Top on my list is this molecular-inspired jewelry (which, by the way, includes cufflinks, key chains, tree ornaments and more) created by Raven Hanna. During a particularly unpleasant time in her life, Hanna, a molecular biologist, found beauty in the aesthetic of a serotonin molecule and comfort in its symbolic representation of happiness. She made it into a necklace and then had happiness on her at all times. Inspired by the fact that many molecules function in ways that could be adopted as meaningful personal symbols, she began expanding her jewelry-making practice. Hanna wants it to be a way to communicate science to everyone, so she attempts to maintain the scientific integrity of the molecules without losing the aesthetic. As a tool for teaching, she includes a notecard with each piece to explain its underlying molecular function. I suggest sharing some happiness with this serotonin necklace, showing someone how much you rely on them with these DNA/RNA base pair friendship necklaces, or poke fun at that friend who drinks too much coffee with these caffeine earrings (and Mom… if you’re reading this). Hanna also features an annual holiday special: this year is vanillin, last was cinnamaldehyde. Some of the other molecules include chlorophyll, dopamine, oxytocin, testosterone and theobromine. I’ve included some other science-inspired jewelry after my top 5 (see # 15 and 17). Number 2 Second on my list are these pencils that become plants…but not just any plants, tasty plants. Instead of throwing away your pencil when you can no longer hold it, you can plant it in a small pot and get one of 12 delicious herbs for your kitchen: basil, coriander, dill, mint, rosemary, sage, thyme, cherry tomato, green pepper, calendula, marigold or forget-me-not. Pairing some of these pencils with a small planter for the chef or the foodie in your life would make a thoughtful gift (or as the company responsible, Sprout, suggests, to help the friend who chews on the ends of pencils kick the habit). Sprout is also working on offering a “plant your paper” product. With this, you can send someone flowers with no more than a card or an invitation. Note: Be conscientious of what type of flower you are sending and where (I don’t want to be responsible for encouraging any exotic species introductions!). Number 3 The Book of Barely Imagined Beings is third on my list. It is an award-winning book by science and environmental journalist Caspar Henderson. You may have heard of Jorge Luis Borges’s 1957 Book of Imaginary Beings in which over 100 creatures from myths and folklore were compiled into one book with sketches and descriptions. Borges included many familiar mythical creatures such as fairies or Lewis Carroll’s Cheshire Cat, to lesser-known creatures such as hippogriffs and mandrakes (both of which were recently made famous by J.K. Rowling… sorry Buckbeak, you weren’t the first). Henderson read this book and became hung up on the fact that many of these fantasy creatures, products of the human imagination, weren’t actually that strange. And that’s how he came up with the idea for The Book of Barely Imagined Beings. In the introduction Henderson quotes Richard Feynman: “Our imagination is stretched to the utmost not, as in fiction, to imagine things which are not really there, but just to comprehend those things which are there” to suggest that evolutionary theory makes the world a clearer place, and a place in which our imagination may be actually be stretched further. Really, it’s just as Darwin said: “there is a grandeur in this view of life”. Evolutionary biology is a major theme throughout this grown-up alphabet book, in which Henderson presents one real creature (extant or extinct) for each letter, A-Z. For each animal, he presents a bit of natural history and evolution, as well as a bit of culture, philosophy and historical human behavior towards the animal. This large 448-page book is awesome for anyone who has any kind of interest in anything! Number 4 The fourth gift idea on my list is a bit pricier ($160), but would be a great (and an admittedly selfish) gift for a family member. Give them the opportunity to participate in science by having their mitochondrial DNA sequenced and also the opportunity to get information about their ancestry with National Geographic’s “The Genographic Project”. What you physically give is the “Geno 2.0 DNA Test kit”. But what you’re actually giving is amazing information about ancestry— this includes information about ancestral migration paths and the percentage of the genome associated with different regions of the world. All they have to do is swab their cheek and send it to the project’s scientists for analysis of nearly 150,000 DNA markers. There is a lot more to this project (what they do with the money, information about confidentiality, etc.) that you can read about on the site. Number 5 The last thing on my list made the cut because, in my mind, it’s a classic. Giant Microbes, if you haven’t heard, are giant stuffed toys (microbes) enlarged about a million times their actual size. These are not only hilarious (check out one of the two Valentine’s Day packages –“Heart Burned” which includes Herpes, Pox, HPV, Chlamydia and Penicillin) but they’re also educational (they come with a photograph and information about the real microbe). Their normal size fits in your hand, but they come in “mini” (~3 inches) and “gigantic” (~2 feet). There is also a holiday-package of microbes embellished with elf-ears, candy-canes, reindeer antlers, mistletoe, etc. Try a brain cell (neuron) for your brainy friend, a bookworm (Anobium punctatum) for your bookworm-friend, or yeast(Saccharomyces cerevisiae) for your beer-loving friend. That’s it for my Top 5. But here are some additional suggestions:

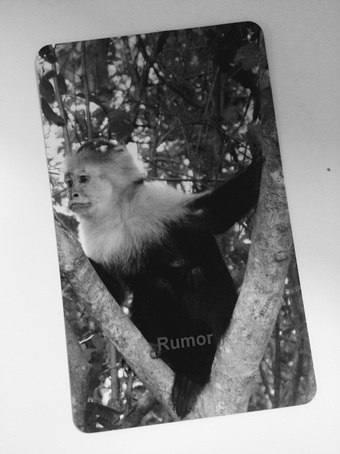

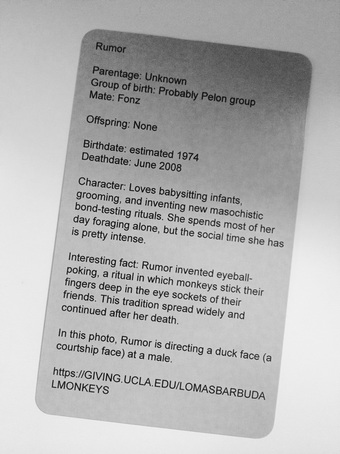

6. Anything from biopop.com. But realistically, the gift idea from this site that caught my attention was dinopet— an apatosaurus-shaped micro aquarium used to hold bioluminescent dinoflagellates. Dinopet may be the only affordable gift on the site, but while you’re there, at least look at the cool DNA wall-art. 7. Give the gift of discovery again (like #4), but this time, in exploring the microbiome! 8. These cosmological-inspired pillows by “geographyhandmade” (also a few inspired by Ernst Haeckle and terrains). 9. These scientific wooden cutting boards by “Elysium Woodworks”. 10. This test-tube tea infuser. Along these lines, mugs are another classic… 11. A water-powered bedside clock (some even have function as a vase). 12. If you like the Dinopet idea (# 6), but not the Dinopet itself, check out these Eco-spheres. These self-sustaining ecosystems contain shrimp, algae and bacteria. They look quite nice on a shelf. Had I made a top 6, this would have made it. 13. The book An Ocean Garden: The Secret Life of Seaweed by Josie Iselin: a collection of flatbed scanner images of over 200 algal specimens collected from the coasts of California and Maine. 14. The book EarthArt, by Bernhard Edmaier: a collection of photographs of the earth surface divided into color-coded chapters, explaining “how, where and why” of the colors. 15. This cool skull jewelry that has been created from CT scans of real human and animal skulls. 16. If you know someone who is into 3D printing, you could gift up these instructions to 3D-print-your-head-and-make-a-beer-mug! 17. This cool ceramic science jewelry inspired by biology, anatomy and microbiology. 18. This I “heart” Science tee, or other science-inspired tee-shirts from “nonfictiontees”. That’s it for this year. It would have been easy to keep going… so we might make this an annual feature. Please leave comments and include links to your favorite science gifts! This week I have been enjoying my time leading introductory biology students on field trips around campus. I have also been enjoying reading what they learn on these field trips in their lab reports. In fact, I'm enjoying it so much that I was inspired, for the first time in my life, to write a poem. Thanks to whoever wrote quiz questions 7a. and 7b. asking for an (a) abiotic and a (b) biotic factor. And thanks to my tuesday 11am class... for each word in the poem belongs to you. The poem is called "Rocks". This cute Capuchin monkey is named Rumor.

As the above card states, Rumor invented a really fun game: grab the finger of your best friend and stick it deep inside your eye-sockets for thirty minutes or so, and then do it again tomorrow! This card is a party favor from the 25th anniversary celebration of the UCLA Capuchin Monkey project, an evening full of power, envy, lust and greed, traditions, trust and treason (just as advertised!). It took a few years for Rumor’s game to catch on. Strange, I know, you’re thinking that this game would catch on immediately in your group of friends. But, the point is, what if Dr. Perry and her team had showed up to study these monkeys for only two years? A smaller snapshot in time would have provided misleading information about this social tradition. They might have thought these monkeys had always jammed their fingers deep into each other’s eyes and missed that it was the invention of a single individual. They could have missed that this tradition took a few years to catch on and misunderstood how the tradition continued after Rumor’s death. And that’s just one example. Given the nature of the celebration, the underlying theme to the evening was the importance of long-term studies. The panel discussion at the end of the evening highlighted the unfortunate fact that long-term research is the exception rather than the rule. There are clear reasons for this, perhaps most of all the difficulty of maintaining studies that exceed the length of time for funding cycles, and maintaining a functional family life. Dr. Wright, who spoke about her work with lemurs later in the evening, also shared her difficulties in maintaining her long-term research while confronting political issues in foreign countries. Congratulations to anthropologist Susan Perry, for her incredible long-term work on Capuchin Monkeys. By the end of her presentation she revealed that her research has featured 567 monkeys and 151 researchers! I applaud Dr. Perry for her presentation as well, though that she is a good speaker perhaps shouldn’t be a surprise: she studies primates and clearly knows how to engage a room full of them. She traced the evolution of her 25-year project one year at a time and by presenting each year’s shocking new discoveries as newspaper headlines. For example, she disclosed the drama from year 7 with the headline: “Ichabod assassinated: a killing one of their own!”, then the drama of year 10 with an equally shocking headline about infanticide. All in all, interesting night. Thanks also to Dr. John Mitani and Dr. Patricia Wright who spoke following Dr. Perry’s talk to present their work on chimpanzees and lemurs. I spent a lot of time this summer thinking about my future career and communicating out loud not in English. Two things to understand about me: First, I’ve wanted to follow just about every career path imaginable. This means that I fall hard into the category of graduate student who wants a PhD one week but not the next (and on those weeks I daydream about what type of menu I would create for my new food truck business). Second, I am not confident in expressing my thoughts out loud… somehow what I’m thinking, no matter how clear in my head, comes out as jumbled thoughts that maybe express something similar to what I mean. The time that I spent reflecting left me resigned to the fact that I probably can’t give my all to both the PhD and the food trucking industries at the same time. But I’m okay with that, because what I really want is to incorporate photography and communication into my science career. Sounds strange, right? I tell you that I am not confident in expressing my thoughts out loud and proceed to tell you that I want to communicate science. Well, my experiences speaking more French than English this summer reminded me of the importance of being able to communicate despite language barriers. It reminded me that the language spoken around the biology department is more like a regional dialect. This made me feel okay about the fact that I am a better communicator on paper. A little story: In forgetting the French word for pig (porc), and the others not understanding the English word pig, there was nothing left for me to do but to describe it as quickly as possible in the simplest way possible. I managed to say, “the little pink animal with the nose like this [imagine me pushing my nose gently towards my forehead with my pointer finger]”. I savored the small giggle I got, and then quickly continued the story. I couldn’t always do this. A few years ago, the conversation would have been frozen. The English word “pig” would have been playing on repeat in my head and I would have said, “never mind” and my story would have been left untold. A pig is something that is widely recognized, even if the specific term to describe it is spoken in a foreign language. What if my inability to explain something as simple as “pig” had made this story end? Non-scientists do not not speak our heavy dialect. An obvious example is the word “theory”. To the general public, theory means a hunch, an idea or speculation. Microsoft Word even gives “belief” as a synonym for “theory” But there are less obvious examples that we may not think about as often, or ever. For example, phrases that use the word “positive” are misleading: A “positive trend” means we are headed towards an optimistic future, right? A “positive feedback” means we received words of praise for our experiments, right? As scientists, we are well versed in statistics and understand that a positive trend means upward and increasing, not necessarily “good”. We know that a positive feedback is a self-reinforcing brutal cycle, not necessarily a good one. An inability to translate our science should not prevent our ideas from being exposed. As a young scientist, I can still remember back to my early days in college when I first began to read scientific papers. Those first few papers were always printed and covered in written definitions, the bulk of each paragraph was underlined or highlighted. I used all five colors of highlighter that came in the pack. Now these documents are saved as PDFs all over my computer’s desktop and hard drive. Before, I was just learning the language. If the public doesn’t understand that they don’t understand our language, we must learn theirs. It takes practice to be good at something. We know how to speak their language, but we need to use it. We can’t continue to use terms like “uncertainty” or “error” in front of non-scientists unless we mean to convey that we made a mistake. I do think that scientists acknowledge the importance of successfully communicating science to the public (for example, recent lab meeting topics have included conversations about citizen science, the “broader impacts” sections of proposals, structuring elevator pitches for scientists vs. businessmen vs. strangers at parties). I also think that we recognize that the public doesn’t really understand what we do. I mean, some of our stand-alone experiments really can sound ridiculous (see this article). I just think we need to actually practice this by encouraging young scientists to blog, to tweet and to write press releases as often as possible using as little scientific jargon as possible. Thanks to my advisor, Casey, for beginning weekly lab meetings with “soooo… who is going to write a blog post?” Only good can come from this. Even though I am not the strongest oral communicator I succeeded at effectively communicating in a different language this summer (and in clarifying my career goals). Sometimes it took more words than I needed, sometimes I had to leave out details, but most times I found a way to describe things so that everyone was on the same page. Even though I don’t remember the ending, I can assure you that everyone who heard my pig story is much better off today. See Communicating the science of climate change by Sommerville and Hassol for some more examples of scientific terms that have a different meaning for the public and for some well formulated thoughts about science communication.

This post was originally made about a year ago on October 10, 2014 on the Ecoevolab blog (ecoevolab.com). A post from my labmate yesterday linked me to this post, and I was struck by how it still resonates with me.

I’m confident in making the claim that most ecologists have wanderlust. Science progresses because of observation and curiosity; and observation and curiosity are both intrinsic to wanderlust. Sociologists have noted the importance of the term as it sits in opposition to structure and organization. As scientists have been herded indoors to spend more time on administrative tasks and to look for money rather than actually exploring and researching freely outside of “the system” (where most of us feel we truly belong), we have been made to have conversations addressing the importance of stupidity in science, researching efficiently, nurturing our creative genes, getting to know thyself, and feeling overwhelmed as a graduate student. Recently, after having some of these conversations around our department, I felt as though we kept talking about the same thing. Don’t get me wrong; each of these conversations was unique and constructive in some way (and there are, of course, strategies to independently tackle these problems). But, I kept thinking about the pink sticky note on my desk. Wanderlust has always been a very whimsical and attractive word to me. Yet lately, after these conversations, the last syllable of the word (“lust”) started to trouble me. “Lust” is typically followed by the words “after” or “for” and usually implies that we can’t have it; that it is something we covet. In her book entitled “Wanderlust, A History of Walking”, Rebecca Solnit writes that “thinking is generally thought of as doing nothing in a production-oriented society, and doing nothing is hard to do. It’s best done by disguising it as doing something, and the something closest to doing nothing is walking.” And there is the problem. Doing nothing but thinking is defensible, but we have to defend ourselves to do it. As Solnit suggests, if we could all do a bit more thinking (real thinking), disguised in an activity that I think we ecologists all innately wish to be doing anyway (walking), I think the issues we spent time discussing can become lesser-issues. For example, on feeling stupid in science: the more I think, the more clueless I feel, and the more comfortable I am with that, the more I feel like I belong in this world of science. Maybe if we all spend more time walking, observing, and thinking, without podcasts or music blaring in our ears, we would all be more willing to accept and embrace the fact that we know very little. Maybe then, grad student morale takes a positive turn, research questions become more creative and interesting… or maybe none of that happens because we don’t come back indoors. As Solnit writes: Perhaps walking is best imagined as an ‘indicator species,’ to use an ecologist’s term. An indicator species signifies the health of an ecosystem, and its endangerment or diminishment can be an early warning sign of systemic trouble. Walking is an indicator species for various kinds of freedom and pleasures: free time, free and alluring space, and unhindered bodies. Wouldn’t it be nice if we could have what we lust after, a little bit more free time? Thomas Jefferson wrote to Elbridge Gerry (he was James Madison's VP) in 1799: Right on, TJ.

image thanks to wikipedia quote verified on monticello's site www.monticello.org When you picture a lazy human, what do you picture? This? Sorry if that stunted your creativity. But what does this guy have in common with Harold (if you haven't met him, see my previous blog post)?

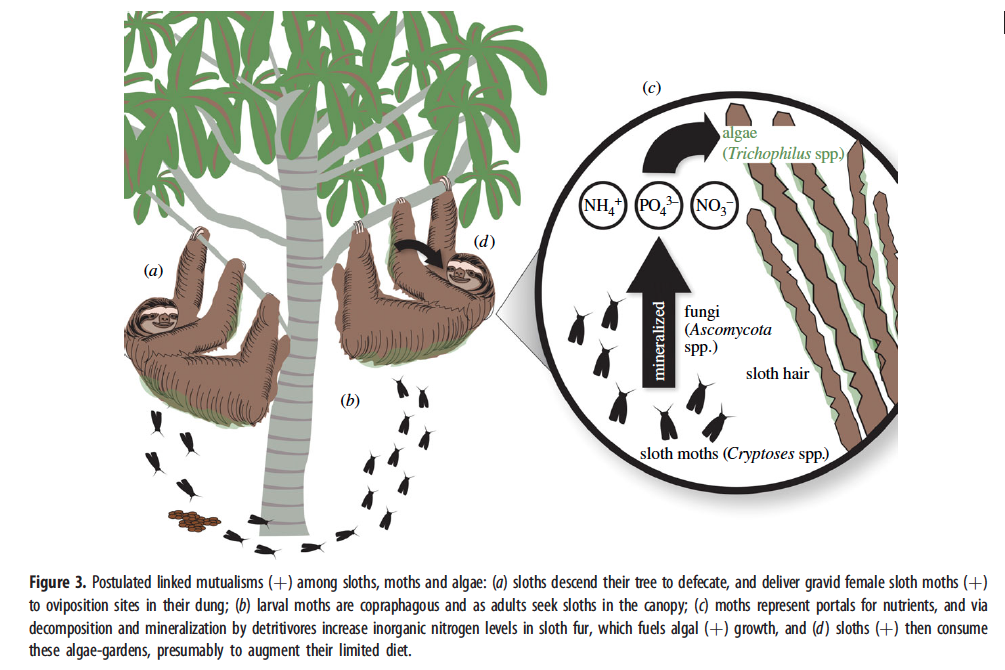

No, definitely not... Only getting up to go the bathroom? Camouflaging oneself in food? Well, kind of. Except these behaviors, for Harold, actually confer fitness benefits. Let me explain with the help of some evidence from Pauli et al. 2014 (A syndrome of mutualism reinforces the lifestyle of a sloth). The three-toed sloth only gets up (or down) to go to the bathroom. He descends from his tree about once per week to defecate. This behavior is both risky (most sloth deaths occur from predation during the descent) and energetically costly (the trip comprises up to 8% of the sloths daily energy budget). If a behavior persists that is energetically costly and dangerous, there must be some fitness benefit from that behavior, right? A mutualistic partner of the sloth, the pyralid moth, very clearly benefits from this risky behavior: The moth uses the sloth fur for habitat and for mating. When the sloth descends from the tree to defecate, the female moth lays her eggs in the dung. There, her larvae are surrounded by ample nutrients to develop into mature adults who can then fly into the tree canopy to find their very own sloth. However, it hasn’t always been clear how or even if the sloth benefits from this mutualism. But, the results from this research show that they do: the act of descending from the tree to defecate provides sloths with a higher number of moths living in their fur. This translates to sloths with higher fur nitrogen content and this nitrogen translates to a higher biomass of algae that live in the sloth. During self-grooming the sloths consume this algae that are shown to be rich with carbohydrates and lipids. Benefit: healthier sloths. Lazy humans and sloths may both only get up to use the toilet and to ensure they are covered in food. However, for humans, going to the bathroom is an arguably safe activity, at least in terms of jaguars. And sure, we might find an additional piece of pizza en route, but you’d have a hard job convincing me of health or fitness benefits resulting from these actions. Therefore, conclusively, sloths win. Harold is an ecologically and evolutionarily fascinating creature, stay tuned for more sloth science. If you follow the NYTimes, you may have read this cool story a while ago. But after I actually read the original publication a few days ago, I had to write about it. So thanks for humoring my personal interests for the day. figure from Pauli et al. 2014

Reference: Pauli JN, Mendoza JE, Steffan SA, Carey CC, Weimer PJ, Peery MZ. 2014 A syndrome of mutualism reinforces the lifestyle of a sloth. Proc. R. Soc. B 281:20133006.

|

Let's see, shall we.CategoriesArchives

October 2020

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed